by Midnight Freemasons Founder

Todd E. Creason°

“If

you're hanging around with nothing to do and the zoo is closed,

come over to the Senate. You'll get the same

kind of feeling

and

you won't have to pay.”

~Bob Dole

He never forgot where he’d come from nor

what he’d been through during the war. Both of those made him into the man he

later became.

He

came from simple, Midwestern, small-town beginnings during the Great

Depression. He knew all about poverty because he’d lived it. But he escaped and

made his way in the world. Years later, in his plush Senate offices in

Washington, D.C., he kept a picture of his father in Key brand bib overalls to

remind him of his humble beginnings. His father had worn bibs to work everyday

as he toiled countless hours in the creamery and in the grain elevator, making

barely enough to support his family. His father’s words never left him: “There

are doers, and there are stewers.” His father was a doer, and so was he.

He also carried the reminders of his World

War II experiences. His right arm, withered from the wounds he’d received so

many years before, wouldn’t allow him to forget. He’d received the wounds in

the flash of a second, hit in the back and the arm with a burst of machine-gun

fire. He’d waited for nine hours on the battlefield before receiving medical

attention. Even as strong as he’d grown during his hardscrabble youth, he

wasn’t prepared for the battle he’d go through to survive his horrendous

injuries—with infection and complications threatening his life at every turn. In

the end, his right arm was paralyzed—he never regained the use of it. His two

Purple Hearts and the Bronze Star were little compensation.

He was wounded as a young lieutenant in the

10th Mountain Division during an assault against a Nazi fortified

position in the Italian Alps. The assault was scheduled, then delayed a day

because of the death of the President of the United States—Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

As sad as he was at the loss of such a great President, he couldn’t help but

wonder, during his long recovery—What if Roosevelt hadn’t died on that day? What

if the assault had been launched on time? Would I still have been wounded?

His

recovery was hard, both mentally and physically. He was in an army hospital for

three years and three months. There were times he felt bitterness about what

had happened and times he felt sorry for himself. But eventually, he was able

to take that long, painful, mentally challenging experience and turn it into

something positive because one of the things he learned was that he wasn’t the

only one who’d been badly injured—war created many casualties. He was one of

tens of thousands who came home from the war disabled and scarred for life.

He ran for public office and was elected to

the United States House of Representatives. He spent eight years there before

moving to the United States Senate in 1969. He gave his maiden speech before

the Senate on April 14, 1969, twenty-four years to the day from when he was

wounded during World War II. The first thing he did as a senator from Kansas

was to call for a Presidential commission on people with disabilities—using

personal experience to explain that the disabled form a group that nobody joins

by choice, but “It’s an exceptional group I joined on another April 14, 1945.” It

took more than twenty years, but his persistence paid off. In 1990, Congress

passed his bill—the Americans with Disabilities Act. It was only one accomplishment

in his long career, but it was one with deep personal meaning for him in his

decades in Washington, D.C.

His name is Senator Bob Dole.

Dole

was born in Russell, Kansas, on July 22, 1923, to Bina and Doran Dole. His

father worked hard to support his family, but they lived in dire poverty during

the Great Depression. He ran a small creamery and later worked long hard hours

at a grain elevator. In order to survive the tough economic times, the Dole

family moved into the basement of their home so they could rent out the rest of

the house.

Dole

was a star athlete at Russell High School, graduating in the spring of 1941. He

enrolled at the University of Kansas, where he studied law and earned a spot on

the Kansas basketball team under the legendary Jayhawks coach, Phog Allen. But

Dole's study of law at Kansas was interrupted by the onset of World War II. He

would continue his education after his long recovery from the wounds he’d

received during the war.

Dole ran for office for the first

time even before he finished his college degree. In 1950, he was elected to the

Kansas House of Representatives. After serving a two-year term, he returned to

school, earning his law degree from Washburn University in Topeka, Kansas. In

1952, Dole was admitted to the Kansas bar and began a law practice in his

hometown of Russell.

During

the time he practiced law, he also served as the county attorney of Russell

County for eight years. Dole was elected to the United States House of

Representatives from Kansas' 6th Congressional District in 1960. In 1962, his

district in central Kansas merged with the 3rd District in western Kansas to

form a sixty-county district, the 1st Congressional District that soon became

known as the “Big First.” Dole was reelected, without serious opposition, for

three terms as representative for the “Big First.”

In 1968, Dole moved to the United States Senate. He’d defeated

Kansas Governor William H. Avery for the nomination. He remained in that

position for five terms, resigning his seat on June 11, 1996, so that he could

focus his attention on his Presidential campaign. As senator, he’d faced only one

serious challenge to his reelection. In 1974, Congressman Bill Roy launched a

well-financed campaign against Dole. Roy’s popularity was in response to post-Watergate

fallout. In a very close and hard fought campaign, Dole emerged victorious but only

by a few thousand votes.

When

the Republicans took control of the Senate after the 1980 elections, Dole

became chairman of the Finance Committee, serving from 1981 to 1985. When

Howard Baker of Tennessee retired, Dole served as leader of the Senate

Republicans as both the majority leader and the minority leader until he

retired in 1996.

Dole

had a moderate voting record, often being able to bridge the gap between the moderate

and conservative wings of the Kansas Republican Party. He appealed to moderates

by supporting several major civil rights bills. He appealed to conservatives by

voting against several of President Johnson’s “Great Society” bills, but he

joined liberal Senator George McGovern in a bill to lower eligibility requirements

for federal food stamps, a bill that appealed to Kansas farmers.

In 1976, Dole ran unsuccessfully as

a vice presidential candidate with President Gerald Ford. He was chosen to

replace incumbent Vice President Nelson Rockefeller who’d decided to withdraw

from consideration the previous fall. An unfortunate remark Dole made during

the vice presidential debate torpedoed his candidacy: “I figured it up the

other day: If we added up the killed and wounded in Democrat wars in this

century, it would be about 1.6 million Americans — enough to fill the city of

Detroit.” The backlash from the remark hounded him for decades. In 2004, Dole

admitted that he regretted making the statement.

He

made an unsuccessful run for the 1980 Republican Presidential nomination,

unable to overcome the popularity of the leading candidate from California. After

a loss in the New Hampshire primary, where he received only 597 votes, he knew

he was beaten and immediately withdrew. Ronald Reagan won the nomination and

the Presidency.

But

Dole wasn’t done with Presidential politics yet. He made a more serious and

better organized bid in 1988. He solidly defeated Reagan’s vice president, George

Herbert Walker Bush, in the Iowa caucus. Bush finished last in the three-man

race, behind television evangelist Pat Robertson. However, Bush came back

strong to beat Dole in the New Hampshire primary. Dole and Bush differed very

little on the major issues, but the New Hampshire contest came out in Bush’s

favor, partly due to Bush’s television ad campaign that accused Dole of

“straddling the fence” on taxes. The New Hampshire primary hurt Dole, not only

because he lost it but because during a television interview with Tom Brokaw after

the returns had come in, Dole appeared to lose his temper on national

television. Dole was in New Hampshire, and Tom Brokaw and George Bush were in

the NBC studio in New York. During the interview, Brokaw asked Bush if he had

anything to say to Dole. Bush said, “No, just wish him well and we’ll meet

again in the south.” Dole, apparently taken off guard by being interviewed with

Bush, responded harshly to the same question, “Yeah, stop lying about my

record.” The angry remark slowed the momentum of his campaign. Bush defeated

him again in South Carolina, gaining the nomination and eventually the

Presidency.

But

the always persistent Dole wasn’t done yet. He came out strong in the 1996 race,

the early front runner for the nomination with at least eight candidates

running for the nomination. He was heavily favored to win the nomination against

the more conservative candidates, but New Hampshire would prove a difficult

challenge for Dole yet again. The populist candidate, Pat Buchanan, beat Dole

in the early New Hampshire primary.

But

Dole eventually won the nomination, becoming the oldest first-time Presidential

nominee at the age of seventy-three—about the same age Ronald Reagan was during

his second bid for the White House. The win was a long time in coming. In his

acceptance speech before the Republican National Convention, he said, “Let me be the bridge to an America that only

the unknowing call myth. Let me be the bridge to a time of tranquility, faith,

and confidence in action.” In the months that followed, the remark would

be turned around by his adversary, Bill Clinton, whose response to Dole’s

remark was, “We do not need to build a

bridge to the past, we need to build a bridge to the future.” It was

Dole’s toughest fought battle. He resigned his Senate seat to focus on

the campaign, saying he was heading for either “the White House or home.” It

was home.

The

incumbent, Bill Clinton, had no serious primary opposition from the Democratic

Party. Clinton won the election in a 379-159 Electoral College landslide. He

received 49.2 percent of the vote against Dole's 40.7 percent. Dole is the only

person in the history of the two major U.S. political parties who was his

party's nominee for both President and vice president but who was never elected

to either office.

But, unlike the comment Bill Clinton

made during the election, Bob Dole was never about building a bridge to the

past. Throughout his long career, he built bridges to the future. For example,

the Americans with Disabilities Act, a major civil rights victory, outlawed

discrimination in the hiring of qualified people with disabilities. It required

all public buildings to become accessible by providing such things as wheelchair

ramps and automatic doors. It made public transportation available for people

with disabilities. It protected not only those with injuries but also those who

were blind or deaf or who had debilitating diseases. Because of the passage of

the bill, disabled Americans, for the first time, had rights—rights to

employment opportunities, communication, education, and the same public access

most Americans take for granted.

Another of Dole’s pet projects was

the building of a memorial dedicated to World War II veterans on the National

Mall. The Vietnam Memorial had been finished in 1982, but there was no memorial

on the Mall for the veterans of World War II. After his loss to Bill Clinton in

1996, Bob Dole threw his support into raising the $100 million dollars needed

to build the memorial, becoming the leader and spokesperson for the national

campaign. The funds were raised in part by veterans and veterans groups,

including the American Legion and the Veterans of Foreign Wars. Funds were also

raised at small community fundraisers, sponsored by groups such as the PTA, the

Cub Scouts, and the Sons and Daughters of the American Revolution. The money

came from big cities and small towns, a nickel and a dime at a time from

collecting aluminum cans and from countless pancake breakfasts, chili dinners,

fish fries, and bake sales. Slowly, the efforts from all over America paid

off—five million, ten million, twenty million, fifty million . . .

President

Clinton, who obviously respected his former adversary a great deal, appreciated

the fact that Dole’s new cause was a worthy one. Clinton believed that

Washington, D. C., did need to have a national memorial for the valiant men

who’d fought in World War II. President Clinton awarded Bob Dole the highest

civilian award—the Presidential Medal of Freedom. On the same day he awarded

Dole that medal, he unveiled the plans for the World War II National Memorial

on the Washington Mall. Bob Dole, who was there to receive the medal, quipped,

in typical fashion, that he’d hoped that he’d been called to Washington to

accept the key to the front door of the White House.

Later, the elder statesman, in an

emotional speech at the White House said, “I’ve seen American soldiers bring

hope and leave graves in every corner of the world. I’ve seen this nation

overcome Depression and segregation and communism, turning back mortal threats

to human freedom.” In many respects, he was speaking from his own experience.

Because of Bob Dole’s leadership,

the efforts of many supporters in Washington, D.C., and the contributions of

millions of Americans, the nation has a World War II memorial on the National

Mall, located at the end of the reflecting pond at the base of the Washington

Monument. It opened to the public on April 24, 2004—twenty-two years after the

Vietnam Memorial Wall was completed in 1982. The World War II Memorial features

fifty-six pillars, representing the forty-eight states in 1945 where American

youth were drafted and the provinces where Americans lost their lives during

the war. The Freedom Wall is a long wall studded with 4,048 stars, each

representing one hundred American lives lost during the war.

Bob Dole has remained busy in his

retirement. He has written several books, including a memoir and two

collections of Washington humor—one featuring funny remarks and jokes told by

politicians and the other a similar collection featuring United States

Presidents.

Dole appears often as a popular political

commentator on shows such as Larry King

Live. He is also never afraid to poke fun at himself as when he appeared on

Saturday Night Live and the satirical

news program on Comedy Central, The Daily

Show with Jon Stewart.

The Robert J. Dole Institute of Politics opened in July 2003

on the University of Kansas campus in Lawrence, Kansas. The institute, which was

established to bring bipartisanship back to politics, was opened on Dole's 80th

birthday. The opening festivities included appearances by such notables as

former President Bill Clinton and former New York City Mayor Rudy Giuliani.

Bob Dole’s great strength as an

American leader is his dedication to the things he believes in and his

tenaciousness in getting things done, no matter how great the challenges, no

matter how long the road, or no matter how impossible the goal may seem. Even

in his retirement, he has continued to lend his leadership and his good name to

those things that mean something to him.

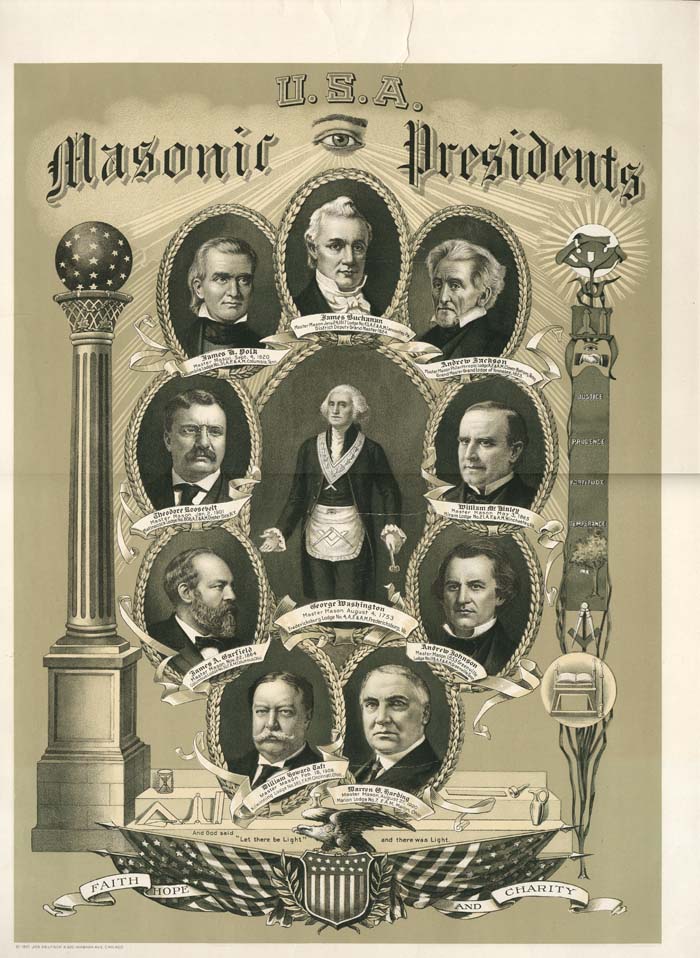

The Illustrious Robert J. Dole, 33° became a member of Russell Lodge

No. 177 in Russell, Kansas, in 1955. He was a member of the Scottish Rite and

was honored as Supreme Temple Architect in 1997.

Brother Dole, a survivor of prostate cancer, has

been a long standing financial supporter of the Kansas Masonic Foundation. Senator

Dole notified the Kansas Masonic Foundation of his desire to create a

Partnership for Life Campaign. He donated $150,000 to create a prostate cancer

research fund at the University of Kansas Cancer Center. To date, the Masons,

through the Kansas Masonic Foundation, have given more than $13.5 million to

the important cause.

This is an excerpt from Todd E. Creason's award winning book Famous American Freemasons: Volume II.

~TEC

Todd E. Creason, 33° is the Founder of the Midnight

Freemasons blog and is a regular contributor. He is the award winning

author of several books and novels, including the Famous

American Freemasons series. He is the author of the From Labor to Refreshment

blog. He is the Worshipful Master of Homer Lodge No. 199 and

a Past Master of Ogden Lodge No. 754. He is a Past Sovereign Master of the Eastern Illinois Council No. 356 Allied

Masonic Degrees. He is a Fellow at the Missouri Lodge of Research. (FMLR) and a charter member of a new Illinois Royal Arch Chapter, Admiration Chapter

U.D. You can contact him at: webmaster@toddcreason.org